This is about AI, I promise; but first, a little history.

L’Histoire So Far

The human impulse is clear: when in doubt, censor and excommunicate

Journalism has always been both an instrument and a target of wealth and power.

1515: Pope Leo X, born the oligarch Giovanni Medici, responds to Gutenberg’s large language machine by decreeing “no work shall be put into print until its text has been approved by the Church.”

1621: Timothy Archer, the first Englishman to print a ‘coranto’—early European newsletters distributed by the merchant empire of Jakob Fugger, the richest man who ever lived—is jailed, because King James I has banned all international news.

1690: the first and only issue of “Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick,” America’s first multi-page newspaper, is published in Boston. The colonial government immediately shuts it down, burns all unsold copies, and declares it “strictly forbidden… to Set forth any thing in Print without License.”

In France, before the Revolution, newspapers were licensed and censored by the crown. Then the nation’s desperate finances led to the Estates-General and the Declaration of the Rights of Man; censorship was abolished; and journalism boomed. “Between 1789 and 1799, over 1,300 new newspapers emerged.” Again they went hand in hand with power. Most of the French Revolution’s key figures—Danton, Robespierre, Desmoulins, Mirabeau, Brissot, Hébert, Marat—were newspaper publishers1, each using their media mini-empires to inspire followers and denounce (and/or call for the mass lynchings of) enemies, until the Revolution became the Reign of Terror and brutal censorship returned.

In independent uncensored America, the invention of political parties and the ‘Party System’ similarly led to a profusion of partisan newspapers; the infamous Hamilton-Burr duel of 1804 was provoked by newspaper attacks.

Governments continued to fight this new information technology with taxes and censorship, but activists such as John Wilkes, along with slow acceptance of the fact that mass censorship is hard to enforce and often counterproductive, made it a losing battle even before the invention of the industrial rotary press in 1814. Then:

The first paper to use this new tech was The Times, which increased its circulation tenfold in a few decades, and invented war correspondence: just as Vietnam was the first televised war, Crimea in 1853-56 was the first reported war, and the public responded with similar outrage. The 19th century also brought The Guardian, The Telegraph, and The New York Times; “penny dreadfuls,” the video games of their day, denounced as horrifically violent and toxic to the minds of youth; and—especially in New York City—so-called ‘yellow journalism.’

The Yellow Journalism Black Box Blues

Even before the legend becomes fact, print the legend; how do you think it gets that way?

The ‘Yellow Kings’ were William Hearst, subject of Citizen Kane, and Joseph Pulitzer, whose name adorns journalism’s most prestigious award — which is ironic, as ‘yellow journalism’ means “unsubstantiated claims, sensationalist propaganda, and outright factual errors.” (The term came from a comic strip, The Yellow Kid, which defected from Pulitzer’s New York World to Hearst’s New York Journal.) Furthermore, “both at the time and in retrospect, critics of yellow journalism saw its sensationalism and dishonesty as a business strategy.”

At its peak Hearst’s newspapers were instrumental in provoking the Spanish-American War. (The infamous Hearst quote “You provide the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war” is, appropriately, apocryphal.) Even those not entirely opposed to the yellow publishers’ goals grew appalled: a 1910 paper, “The Influence Of Newspaper Presentations Upon The Growth Of Crime And Other Anti-Social Activity,” quotes Theodore Roosevelt accusing his era’s newspapers of “habitually and continually and as a matter of business practicing every form of mendacity known to man, from the suppression of the truth and the suggestion of the false to the lie direct.”

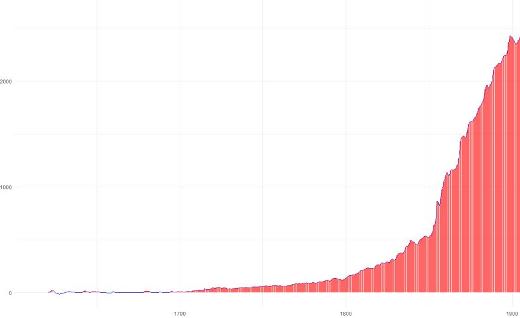

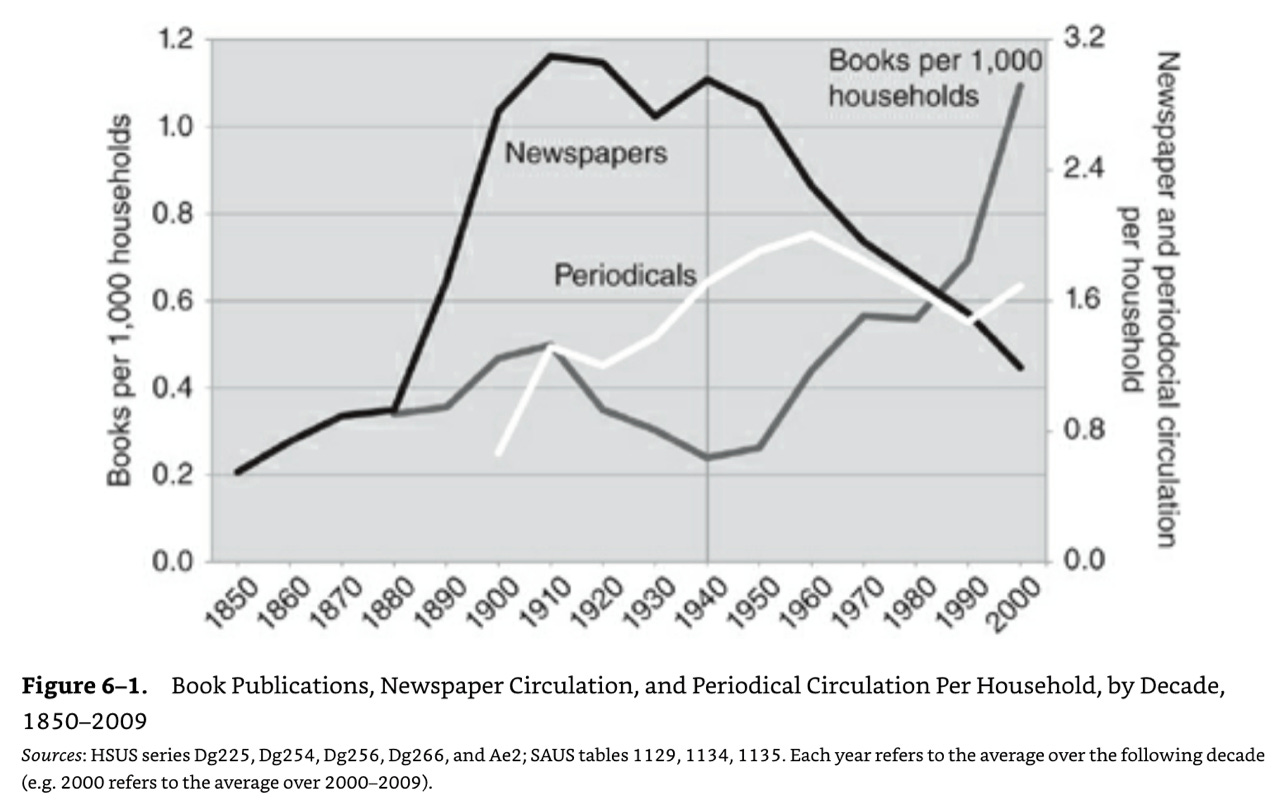

It is hard to overstate the importance of newspapers in the first half of the twentieth century. There were periods when the average household received three papers per day:

Eventually, especially after World War I, public opinion and the courts turned against yellow journalism, and newspapers adopted codes of ethics. They also consolidated into nationwide chains, while radio became the first truly mass medium and ‘newsreels’ shown before movies ushered in the age of televisual journalism. During this confluence of new technologies, between the world wars, journalism, a.k.a. ‘the fourth estate’ became part of the nascent ‘media’ industry … and, across the developed world, a new pillar of establishment power.

This was most explicit in places like the UK and Canada, with the formation of the BBC in 1927 (its first broadcast: a news bulletin) and the CBC in 1936. In the USA, the Communications Act of 1934 created the FCC and required broadcast licensees to act in the “public interest, convenience and necessity.” For the rest of the century there was often a very fine line between government and media elites. Some examples:

the Hays Code, famous for 35 years of Hollywood self-censorship, was named after William Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America … and former chairman of the Republican National Committee.

William Hearst brokered the nomination of Franklin Roosevelt as the Democratic presidential candidate in 1932.

Similarly, Australian newspaper-turned-media baron Rupert Murdoch was instrumental in UK politics, notably in 1992, and also US politics via Fox News.

Ronald Reagan’s first leadership role was the Screen Actors Guild presidency.

Ben Bradlee, editor of The Washington Post during Watergate, was brother-in-law to socialite and journalist Mary Meyer, who married a CIA agent and then became a mistress of President Kennedy—Nixon’s 1960 presidential opponent—before her (unsolved) murder; their social circle also included James Angleton, who headed counterintelligence at the CIA for 20 years.

…but even he was far less connected than his boss Katherine Graham, heiress publisher of the Post (and later Newsweek), daughter of the first president of the World Bank, and a personal friend of Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Reagan.

Broadcast media was regulated far more strictly than print. There was no newspaper equivalent of the FCC. From 1949-1987, the “fairness doctrine” required broadcasters to air multiple contrasting views regarding controversial matters of public interest. The “equal-time rule,” still extant, makes them give equal airtime to political rivals. Conversely, perhaps causally, print journalists were much more effective at unearthing government coverups—My Lai, Watergate, Iran-Contra, etc.

Manufacturing Consent from Limousines

At what point does speaking truth to power become dictating truth from power?

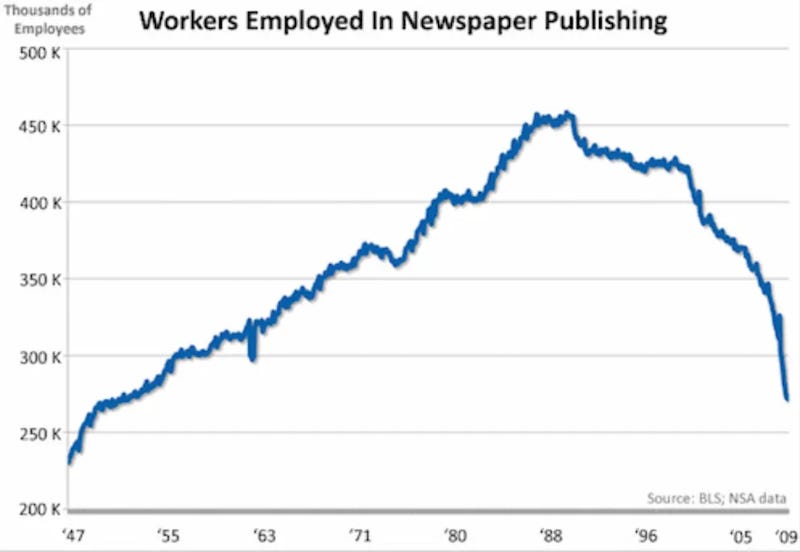

In general, in mid/late 20th-century America, and to some extent Europe, government figures and media moguls alike were members of a loose cohort of elites who shared the goals of perpetuating their status and winning (or at least surviving) the Cold War. The apotheosis of Big Media—America’s major magazines, newspaper chains, and broadcast networks—was the 1980s, when they were fabulously wealthy and enormously powerful. In that era newspapers alone employed roughly 1 in every 300 working-age Americans:

If a single event represented that peak, it would be Newsweek’s 50th anniversary party:

There were 1,600 guests, including President and Mrs. Carter, first lady Nancy Reagan, Mary Tyler Moore, Henry Kissinger, and Andy Warhol … A stage set designed to look like an old-style magazine office featured Jessica Tandy, Lauren Bacall, and James Earl Jones playing journalists … My husband and I were flown from Washington in a private plane … Reporters spent their days wining and dining White House staff; one Reagan staffer was known as "America's guest" because he turned up on so many expense accounts.

Similarly, this was Time in the 1980s:

The first week I was there, the World section had a farewell lunch for a writer who was being sent to Paris to serve as bureau chief ... at Lutèce, the most expensive restaurant in Manhattan, for 50 people. If you stayed past 8, you could take a limousine home ... anywhere, including to the Hamptons. If a writer who lived in suburban Connecticut stayed late writing his article that week, he could stay in town at a hotel of his choice. When the editor-in-chief visited the facilities of a new publication called TV Cable Week in White Plains, a 40-minute drive, he arrived by helicopter—and when he grew bored, he said to his aide, “Get me my helicopter.”

Of course there were pitched battles between journalists and governments during this postwar period—Vietnam, Watergate, etc.—but the institutions did not attack each other. Whether you call it an alliance of convenience among socially intertwined elites, or a Cold War détente, generations passed in which Westerners could pretend that journalism was not about exercising power, and always/only about holding power to account … when in fact, as history shows, it has always been both.

In the 1980s a backlash finally erupted against the immense and barely scrutinized influence of the media moguls. In Manufacturing Consent, in its day a cause célèbre, Noam Chomsky accused the American media of being “ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function, by reliance on market forces, internalized assumptions, and self-censorship.”

Was this true? Maybe! You can certainly make a pretty good case. The Manufacturing Consent documentary remains a fascinating time capsule.

Did it matter? No, as it turned out. Because these enormously powerful institutions at the heart of the most powerful nation in the world would soon have their legs cut out from under them by a handful of engineers and grad students, propelled by nothing more or less dangerous than a prophecy/observation dating to 1965—not that journalists had noticed at the time—called Moore’s Law.

The Tech Industry: Threat or Menace?

Awkwardly the massacre of mass media was only ever an unintended side effect

Media empires were mostly built on advertising. A few exceptions, such as cable TV, relied on subscriptions. Newspapers seemed to have an impressively diverse and antifragile revenue model, using their status as the pre-eminent disseminators of local information to generate revenue from a ‘three-legged stool’ of advertising, circulation (subscription and retail), and classifieds.

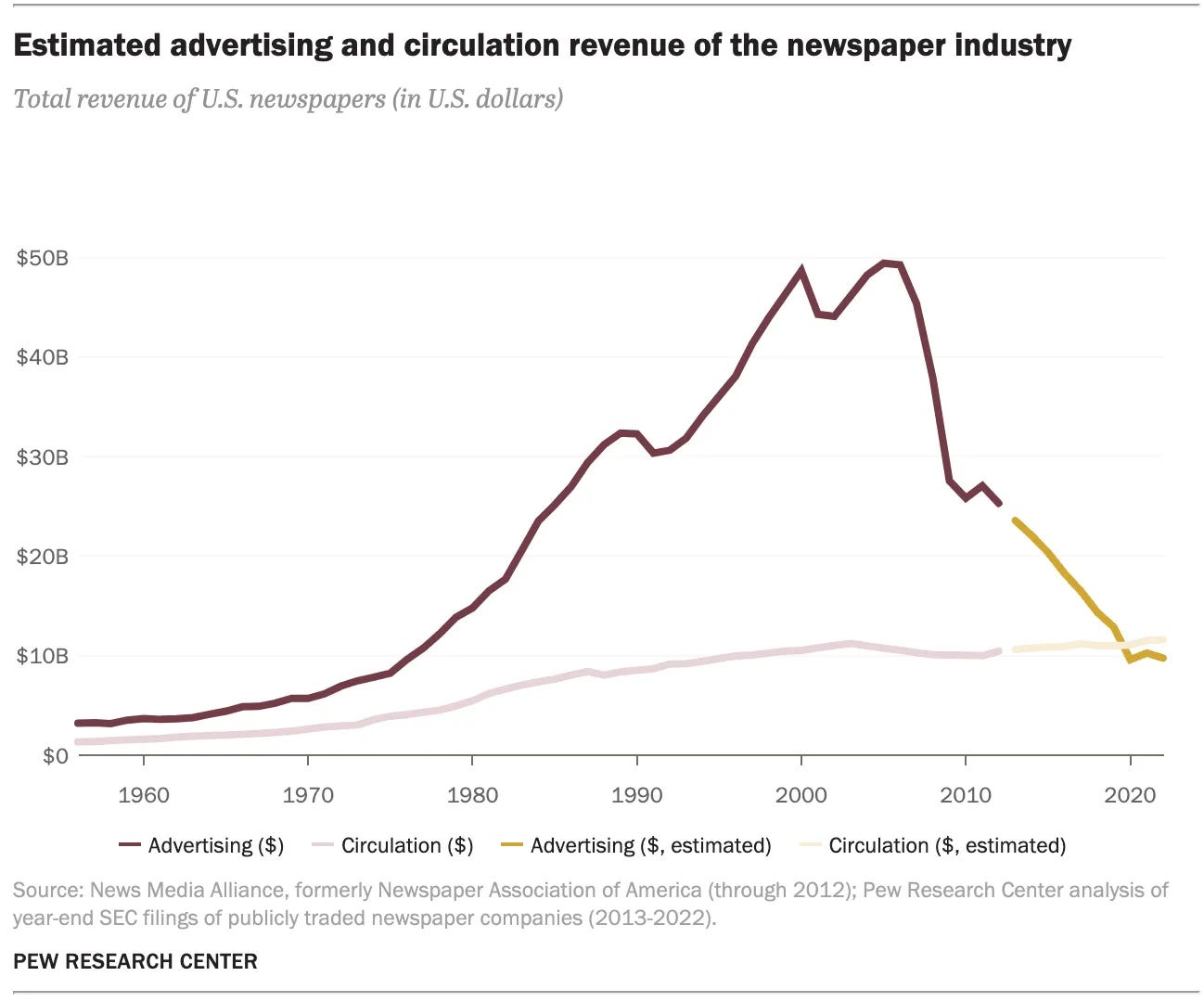

Then Craigslist reduced that third leg to splinters almost overnight. It incorporated in 1999; newspaper income from classifieds promptly plummeted from $19.6 billion in 2000 to $4.6 billion in 2012.2 As for advertising and circulation—

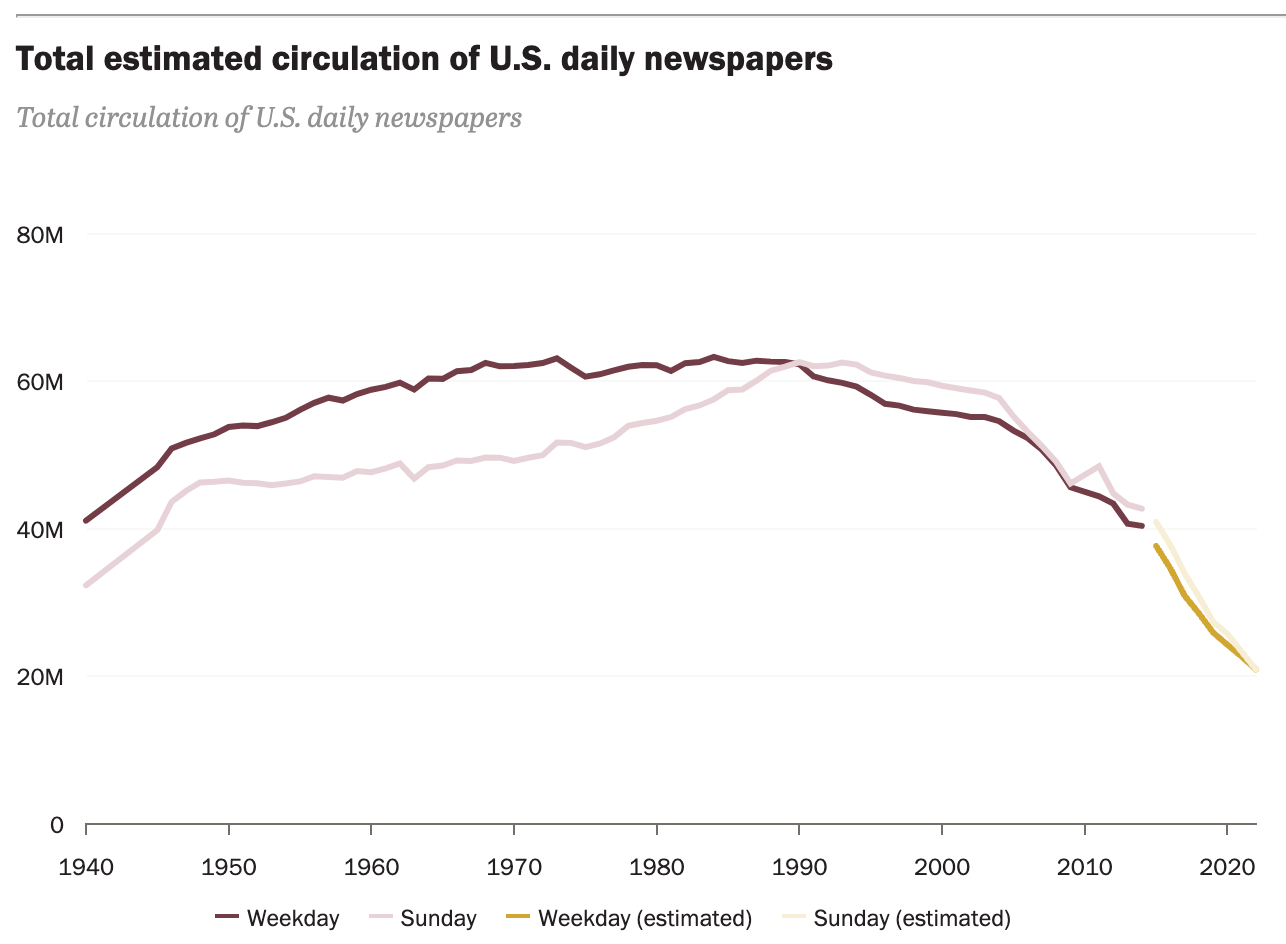

And that’s with price hikes. The raw circulation numbers were far worse—

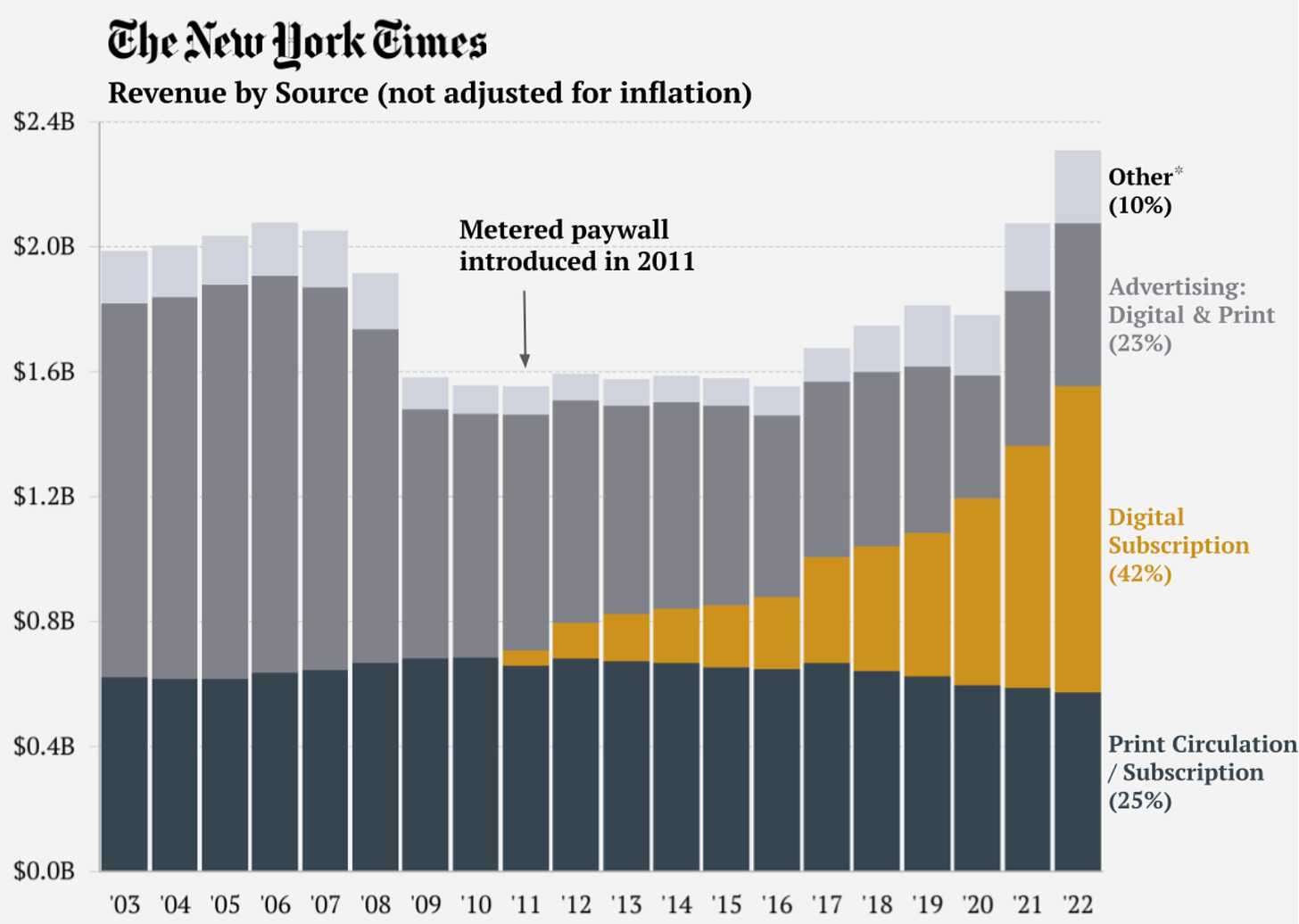

However. While the local-news landscape looks increasingly like Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic-dystopian The Road, a couple of exceptions, notably the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, have managed to thrive, ish, on digital subscriptions:

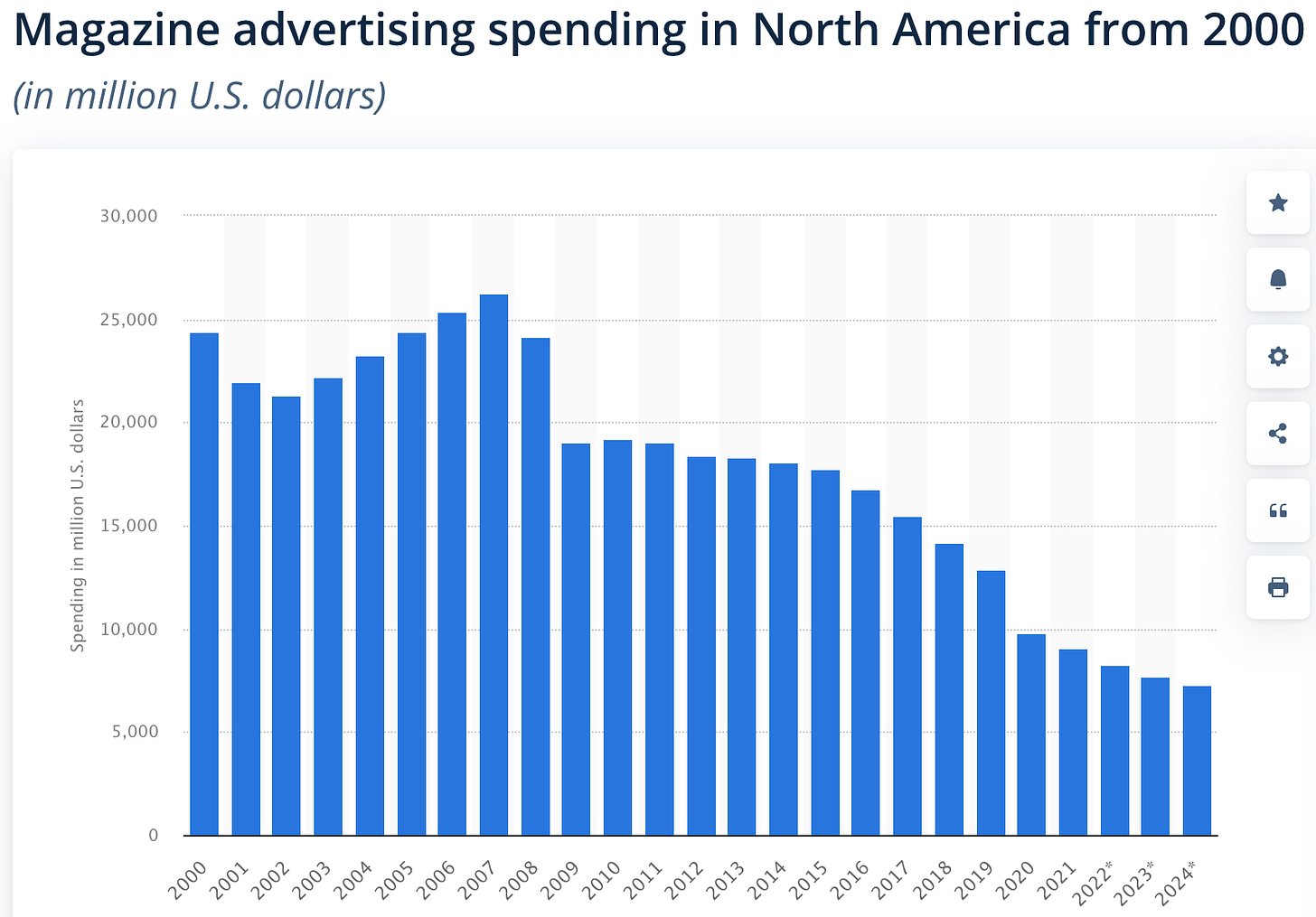

But what happened to newspapers also happened to magazines:

Television held out longer … but last year ‘cord cutters’ who abandoned cable TV for digital streaming became the majority, and digital TV advertising surpassed linear TV.

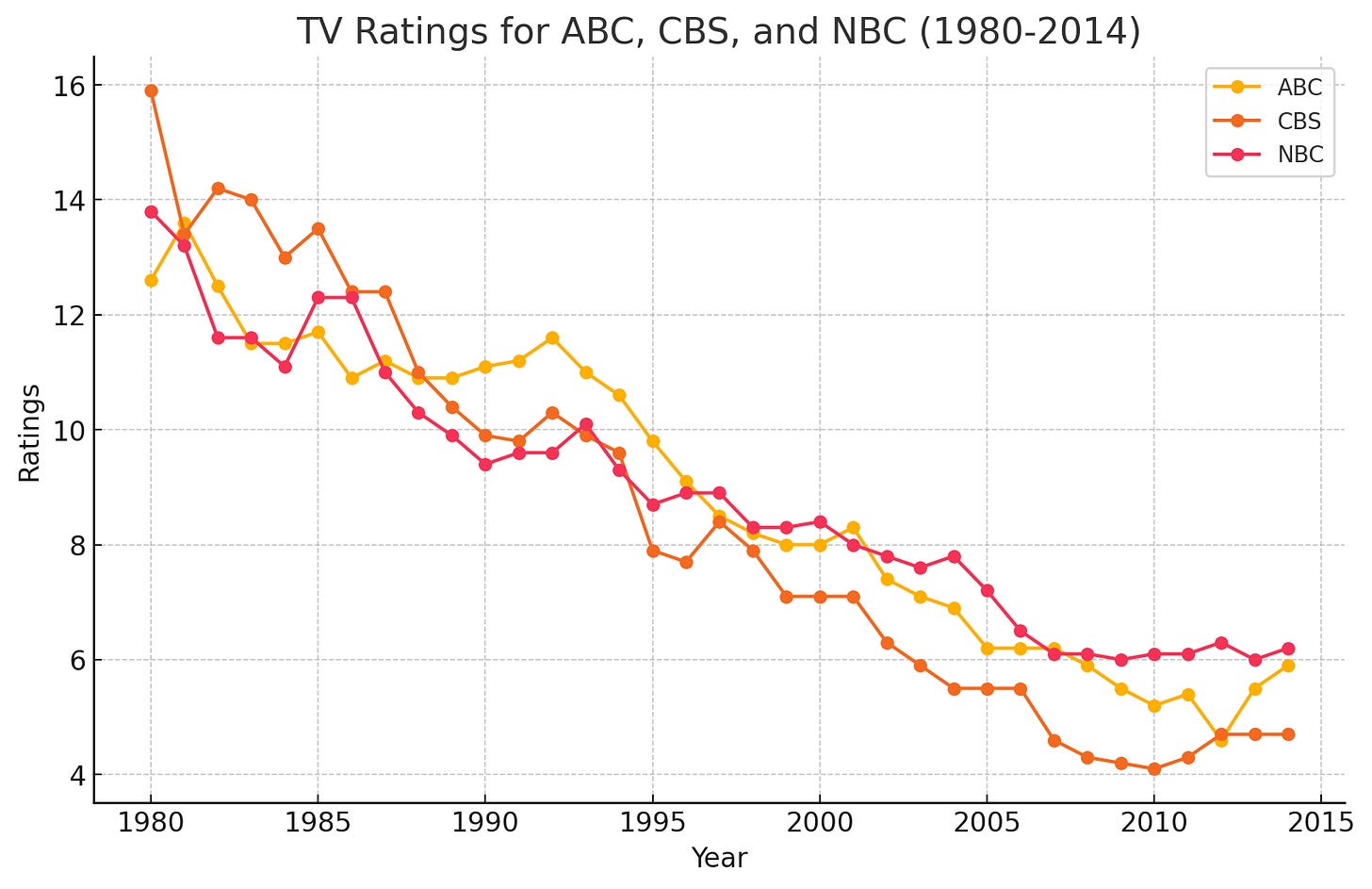

As for network TV: after the 1985-86 television season, the lowest-rated show not cancelled was Airwolf, TV’s 64th most popular show, with a Nielsen rating of 12.5. Want to guess how many shows have hit that ratings mark since 2016? The answer: zero. Every single network TV show over the last seven years would have been considered a ratings disaster, and immediately cancelled, in the 80s.

TV journalism has followed the same trend. 60 Minutes, TV’s flagship journalism program, has fallen from a ratings peak of 28.4—watched by 28% of all American households!—to 6.7. Network news plummeted similarly:

Since 2015 they have actually held up relatively well … at that very low level. But many, many YouTube streamers have much larger audiences than the nightly network news.

Cable news never had as far to fall, and the reach of the major cable news channels stabilized at about 2 to 3 million households. But that’s only ~2% of all US households. CNN’s audience is larger than it was in the 90s but there’s no question its cultural relevance is enormously diminished

What happened to newspapers, magazines, television, and journalism?

I mean. We all know what happened. The Internet happened. Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Netflix, TikTok, and Substack happened.

Strangely, over this same period, journalists began to treat the tech industry extremely critically, sometimes even vindictively, almost as if they now saw it as an enemy. What a mysterious and inexplicable development! I suppose we’ll never know why.

The Digital Demise

Trust is engendered by a common enemy, so if we no longer have one, we manufacture some

I don’t mean to suggest there’s been conscious collusion among journalists to target the tech industry. As I’ve written before: People, including journalists, react in fairly predictable and and understandable ways to provocations. Journalism used to be a secure, prestigious, even lucrative industry; now look at it. Journalists have seen their entire industry, in which they believed, which gave them meaning, gutted by the tech industry. No wonder they tend to be biased against it! And no wonder they’ve subtly, collectively, usually unconsciously, turned the cultural temperature up towards “boiling rage.”

…Having said that, in 2022 Matt Yglesias wrote, in a since-deleted but archived thread, confirmed by Vox’s Kelsey Piper:

A few years ago the New York Times made a weird editorial decision with its tech coverage. … They started covering it with a very tough investigative lens — highly oppositional at all times and occasionally unfair. … This was a very deliberate top-down decision. They decided tech was a major power center that needed scrutiny and needed to be taken down a peg, and this style of coverage became very widespread and prominent in the industry.

Certainly it is true that the tech industry has become an enormously wealthy and powerful engine of change in the world, and as such a valid target of “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” a famous motto among journalists. But another interpretation, given the awkward realpolitik that journalism has always been an instrument of power, is that this was simply a power move—a way for one power center to strike back against an enemy.

You might think: if so, they sure waited a long time!, given that advertising and circulation started nosediving in the oughts. But the NYT (along with a few others like The Economist) were among the few shielded from this, because they benefited from the Internet-enabled consolidation of audiences for quality news.

Indeed there was a period in the 2010s when it seemed the traditional journalism model would hold up in this new era. High-end journalism would be supplied by blue-chip publications like the NYT, WSJ, The Economist, and CNN; a few outliers like The Guardian and Slate; and state-sponsored organizations like Al-Jazeera and the BBC. Smaller niches would be covered by new ‘digital native’ blogs/publications: Gothamist, SFist, Hoodline, etc. for local coverage; Wired, Mashable, TechCrunch, etc. for tech; Buzzfeed, Jezebel, The Toast, etc. for culture; and so forth and so on.

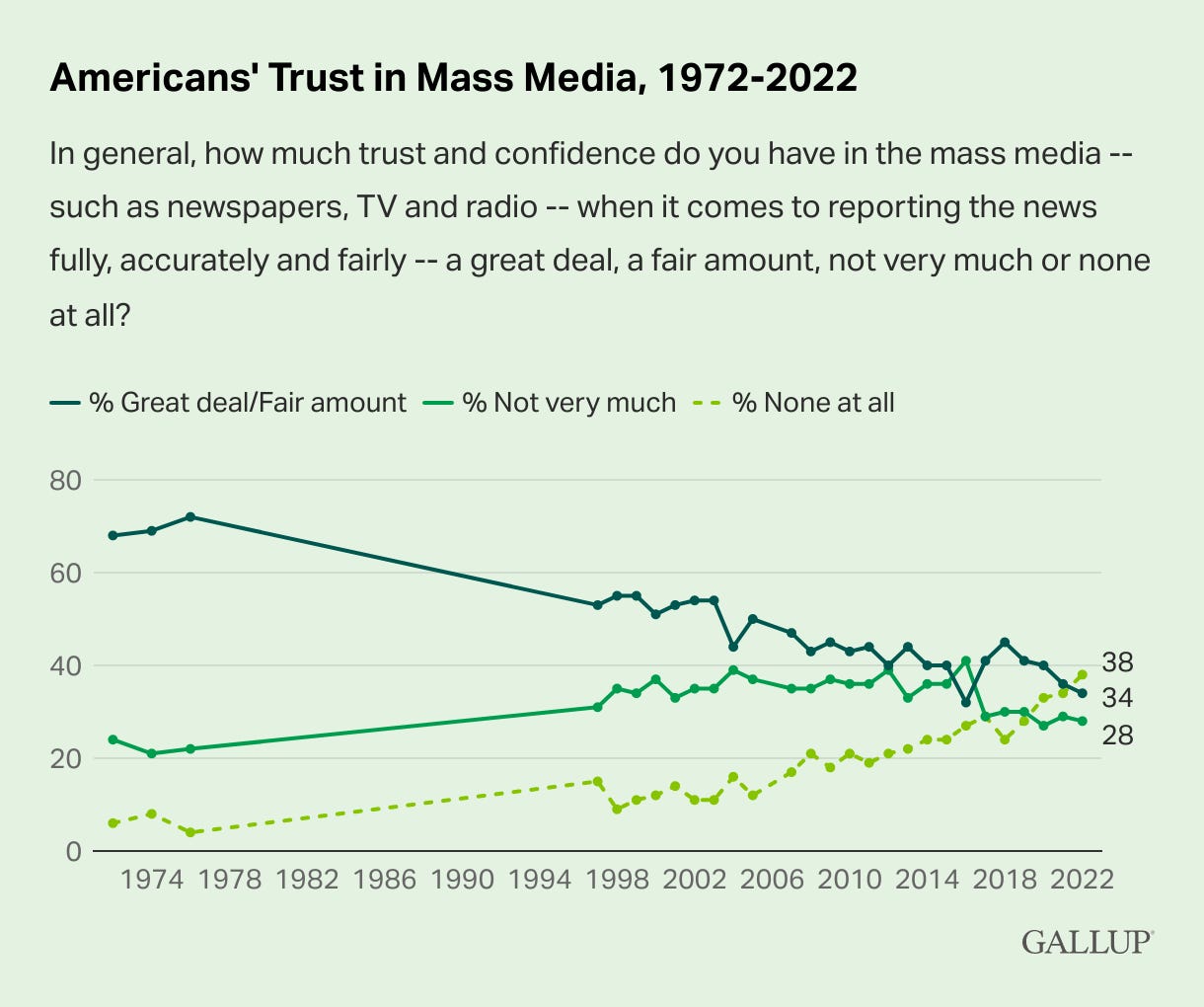

To put it mildly; this did not work. At the high end, the business models remain functional, but fundamental mistrust in journalism as a concept is sky-high and rising:

Those numbers are stark. Fully two-thirds of Americans have either “no trust at all” or “not very much” in media journalism—almost 40% have none at all!—and before you blame Trump, note that this is clearly part of a much longer-term trend.

As for the ‘digital natives,’ those high hopes were soon shattered. Their story is by now cliché: they couldn’t make the numbers work; they made some money off events, but not enough; they tried to ‘pivot to video’ and failed; and after several dispiriting rounds of layoffs, they were sold to some corporate entity that either turned them into a click farm devoid of meaningful journalism, or accepted their losses as part of some larger strategy. Are there exceptions? There are always exceptions. But does anyone still believe in that future? …Not really.

It has also become cliché to refer to the ongoing journalism crisis. This is not correct. Rather, across the world, journalism faces a polycrisis:

plummeting readership/viewership/revenues for all but a very few publications

increasing authoritarian attempts to shape or suppress what is published

rapidly collapsing trust in journalism as an institution

growing failure to attract and retain elite talent

…to name only a few of the most glaring individual crises.

What is to be done?

Running Code and Rough Consensus

When you can no longer pretend to be objective, people notice … and overcompensate.

On the level of realpolitik power, journalism is important because it shapes public opinion. But on the level of getting things done, journalism is important because neither groups nor individuals can understand, coordinate with, or support one another without a shared understanding of the world around them and their positions in it. Journalism provides that shared understanding: a consensus reality.

It helps if that consensus reality is both correct and also widely perceived as correct. It’s very hard to forge it when journalism is increasingly mistrusted.

What journalists need to accept and internalize is that this mistrust is not unfounded. It’s not just the right wing; it’s not just the crazies; it’s not just the tech industry; it’s not just the ignorant. The fault, dear Brutus, lies not in our readers, but in ourselves. The end of the postwar consensus has led directly to untrustworthy journalism.

To quote James Bennet, the (notoriously) former opinion editor of The New York Times, the NYT “promises to serve up the news of the day without any bias.” This is of course absurd. All news is biased, at minimum by selecting which facts and context make it into a story and which do not. It was possible to pretend to report impartially during the postwar period, and to pretend journalism was not an instrument of power, only because the implicit bias was always that of the institutional establishment.3

Today, though, the institutions themselves are under attack, from all sides and from each other. It is not only extremist right-wingers who speak of the ‘deep state’ and the ‘Uniparty’—progressive Scottish author Charles Stross, for instance, wrote “Is the United Kingdom a one party state?” back in 2013. Young people are increasingly skeptical of not just university educations and other institutions but democracy itself. It would be strange if they weren’t skeptical of institutional journalism, itself a pillar of the establishment, and its hypocritical claims of purely objective reporting.

Journalists themselves are beginning to abandon that pretense. Over the last decade there has been, quoting Bennet again, a widespread “breakdown in the boundaries between news and opinion” in newsrooms, along with

an environment of enforced group-think … there has been a sea change over the past ten years in how journalists think about pursuing justice … Illiberal journalists … do not believe readers can be trusted with potentially dangerous ideas or facts … they must be seen to applaud the right sentiments of the right people in social media … What matters, in other words, is not truth and ideas in themselves, but the power to determine both in the public mind.

(That last line … may sound a little familiar in the context of this essay.)

What Bennet doesn’t understand is that the younger generation has not abandoned impartial journalism. Rather, they are engaged in an understandable backlash against the pretense that there ever was such a thing. Noam Chomsky would have approved. Promulgating implicit bias while pretending to be “fair and balanced” like Fox News, or ‘unbiased’ like the NYT, makes a publication far less trustworthy than one that at least admits and embraces its particular viewpoint and stance.4 Ultimately all journalism is opinion journalism. Modern journalists increasingly accept this—

—but what they in turn don’t always understand is that there is a spectrum of bias. On one end, advocacy journalism, you simply choose in advance a side to support, and a side to suppress, and tailor your story accordingly. This is all too common. On the other, evidentiary journalism, you consider a hypothesis, gather evidence, and publish what it says. It’s the difference between a lawyer making a case and a scientist testing a theory. Evidentiary journalism is still biased, not least in the selection of hypotheses and evidence, but it’s far closer to objectivity than outright advocacy journalism.

Alas,

advocacy journalism is both easier and more popular/outrageous

many have misinterpreted ‘all journalism is biased’ to mean ‘all journalism might as well be outright advocacy’

…and then there are those aforementioned “very deliberate top-down decisions” to require “highly oppositional” journalism, e.g. the NYT vs. the tech industry.

So nowadays advocacy journalism is much-to-most of what we get in our various epistemological bubbles—be they left-wing, right-wing, or orthogonal—amid the fragmentation of our previous consensus reality. No wonder our trust is disintegrating!

Everything Doge Is New Again

In which all these written words return us to what looks a lot like oral culture

Imagine for a moment what it was like to live before print journalism:

Information was transmitted as news by word-of-mouth among small groups … In Venice, one could hear local, but also international news on the Piazza San Marco near the Doge's Palace or the Rialto Bridge. This was also possible in London near St. Paul’s Cathedral, in Hamburg or Antwerp near the stock exchange or post office, and in Rome, Paris, Prague or Vienna within the vicinity of the court

This is … strangely similar to how many people get news today? Let me rewrite:

Information was transmitted as news by social media posts or group chats … On Facebook5, one could find local, but also international news on your Feed or in your Reels. This was also possible on certain Discords, on Twitter/X or TikTok in your feed or Explore tab, and in several of your Signal and WhatsApp group chats which touched on current events.

Thirty years ago you would simply read a morning paper and watch the evening news. Now it’s as if we have returned to the word-of-mouth era (with the Internet empowering you to teleport to all of Europe’s various town criers) and the yellow journalism era. I won’t belabor the many lamentations re the sea of misinformation / disinformation / ‘fake news’ out there, “habitually and continually and as a matter of business practicing every form of mendacity known to man, from the suppression of the truth and the suggestion of the false to the lie direct,” to re-quote Teddy Roosevelt.

But misinformation is a demand problem, not a supply problem, and this demand is generated because people who live in the same nation, even the same block, can now also exist in entirely different epistemological realities. Whole cohorts of people, mostly right-wing, are convinced San Francisco is a lawless city wracked by crime and overrun by homeless addicts. (I was there today. It was unremarkable except for the Waymos.) Others, mostly left-wing, believe COVID-19 is still an ever-worsening “mass disabling event” and it’s insane that we’re not all masking everywhere as we did in 2020. Such cohorts are constantly reassured of their correctness by their compatriots inside their epistemological bubble, who also help them reject the cognitive dissonance of contradictory news from outside.

Importantly, these bubbles are formed by two separate forces: attraction, natural clustering among like-minded people, and, probably more importantly, repulsion, the furious rejection of despised outgroup(s). People tend to reject correct information as ‘fake news’ only partly because of its actual semantic content. Often—usually—they’re really rejecting it because it’s something Those Worst People are saying.

This breakdown in consensus reality has also helped spawn conspiracy theories. Given how many consensus bubbles are at least arguable—San Francisco did get kind of feral for a few years, though it’s much better now; long COVID afflicted millions, though thankfully less so today—it’s no wonder we also got Pizzagate, QAnon, etc.

Ultimately there are several hard truths journalists need to accept:

Journalism is always biased, and always to some extent an exercise of power.

Today’s deep and angry mistrust of journalism is not unfounded.

Seeking truth is better than advocating for beliefs, no matter how heartfelt.

and, perhaps the hardest pill to swallow of all—Any solutions will come from their ‘enemies’ in the tech industry.

I Promised This Was About AI

Because journalism, as a collective institution, is in many ways already a language machine

To re-summarize some key points:

Journalism, which creates our shared consensus reality, which we need in order to understand, cooperate, and get things done—all of which are much easier when consensus reality corresponds well to actual reality—is in the midst of a polycrisis.

The rising mistrust of journalism corresponds to the fragmentation of our establishment consensus reality and the increase in advocacy journalism.

Evidentiary journalism is more trustworthy than outright advocacy.

Epistemological bubbles are often driven more by the rejection of despised outgroups than by actual acceptance of ingroup beliefs.

Imagine—and give me some rope—if we could, somehow, despite all the incentives, increase the proportion and quality of evidentiary journalism, while also ensuring that stories are not rejected out of hand because they have been told by Those Wrong People, who for whatever reason engender a very personal and vicious hatred.

How would that work? Well, here’s the really crazy part: imagine if we had some kind of magical narrative machine that could assemble and collate the available evidence for any hypothesis, for all topics and subjects, at scale, automatically. Not only would this greatly improve and increase evidentiary journalism; such a machine wouldn’t suffer from the visceral parasocial hatred that provokes knee-jerk rejection of what Those People say. Even when they rejected its evidence, the rejection wouldn’t be so personal.

Further yet, imagine if every different bubble/cohort had its own magical narrative machine(s) … such that evidence consistently surfaced by all such machines functioned as a shared consensus reality, even while people continued to live in different bubbles.

…I know, right?

…I am aware that proposing AI/LLMs as a solution to any problem, much less a journalism problem, will provoke outraged fury at my obvious bad faith and/or idiocy from people who are convinced it is a fact beyond dispute that modern AI is no-good very-bad horrible. (Which ironically is a superb example of the epistemological bubbles we were just talking about.) I give you some reasons to consider the possibility rather than angrily rejecting it out of hand:

If you think “everybody knows LLMs are spectacularly untrustworthy and hallucinate horribly,” you have a couple of years of LLM engineering practices to catch up on. We’re not talking about asking ChatGPT what it knows. We’re talking about using LLMs to help transform text/image/audio/video evidence into a structured narrative, then itemize each fact in that narrative and verify it against the evidentiary dataset, all of which they can do, automatically, at scale. None of the evidence would come from its interpretation of its training data.

A recent study in Science shows that conversations with a well-engineered LLM system can reduce or even eliminate people’s beliefs in conspiracy theories.

Another study shows that more than half of scientific researchers found GPT-4 generated feedback on research papers to be helpful or very helpful, and 82.4% found it more beneficial than feedback from at least some human reviewers. This seems relevant to their merits in providing evidentiary support to journalism.

Many initial experiments in LLM-enabled journalism are already underway, particularly in science and data journalism, with promising results already, even though we’re still in the infancy of both LLMs and LLM engineering.

A good way to think of today’s LLMs is that they’re like mediocre graduate students. That doesn’t sound exciting, I know. But they are an infinite army of mediocre graduate students who will do whatever you tell them (within limits, in weird and idiosyncratic ways) on demand.

Let’s get really crazy. Let’s imagine five or ten years from now. Imagine a newsroom divided, as they are today, into ‘news’ and ‘opinion.’ Some ‘news’ reports are human-written; many are AI-generated, or at least start life that way, in response to notable developments discovered in reliable datasets; what they have in common is that every factual claim is verified against evidence surfaced (not generated!) by LLMs. The audience can read or view any news story, ask follow-up questions, and see answers based on that network of evidence in near-real-time.

Would this still be biased? You bet. A ideologically opposed newsroom across town will select different subsets of evidence and write very different stories. But both publications would be biased yet perceived as trustworthy—and, perhaps more importantly, would agree on a definable subset of things … a consensus reality.

This is not a mad dream. It is, I would argue, achievable now, with today’s technology.

In Conclusion, AI Is A Land Of Contrasts

The first step towards any solution is to admit that you are a problem

Prophecy is hard and any particular vision of the future, certainly including mine, is always suspect. But I’ve spent the last several months helping to build a tool/platform that uses LLMs for internal corporate reporting, and it is painfully obvious to me that they will be an enormously useful and powerful tool for journalism more generally— none too soon, given the state of journalism today.

Try to imagine the contrary case, in which an extraordinary new technology that can make sense of language, audio, video, and imagery—one that can turn both structured and unstructured data into meaningful narratives, and vice versa!—does not have a profound impact on a vital industry, and pillar of society, that is all about narratives … and that is currently hemorrhaging money, people, trust, and relevance. I think you’ll agree that’s a very hard case to make indeed.

First, though, journalism has to accept that its problems are in part of its own making, and that its solutions will be at least in part technological. The question is: how long will that take, and how much further damage will be done in the interim?

Thanks to Susan Brown and Rohit Krishnan for reading early drafts of this.

For a truly compelling depiction of the French Revolution, and in passing also a depiction of the primacy of newspapers in shaping the course of its events, I urge you to read Hilary Mantel’s A Place Of Greater Safety, one of the finest novels ever written.

It was especially easy during the Cold War, when the implicit bias was “West good, Soviet bloc evil,” because this bias had the advantage of being, relatively speaking, entirely correct.

This is another reason to admire The Economist.

Excellent post. Haven't seen the whole landscape put together before.

Of course I (and maybe you) are biased to see the opportunities for AI in improving the "consensus reality", getting us to "biased but trustworthy", either for individuals, within firms, or for the public. Still, it seems like a compelling case no matter how you slice it.